Q&A: Joe Bun Keo

Q&A: Joe Bun Keo

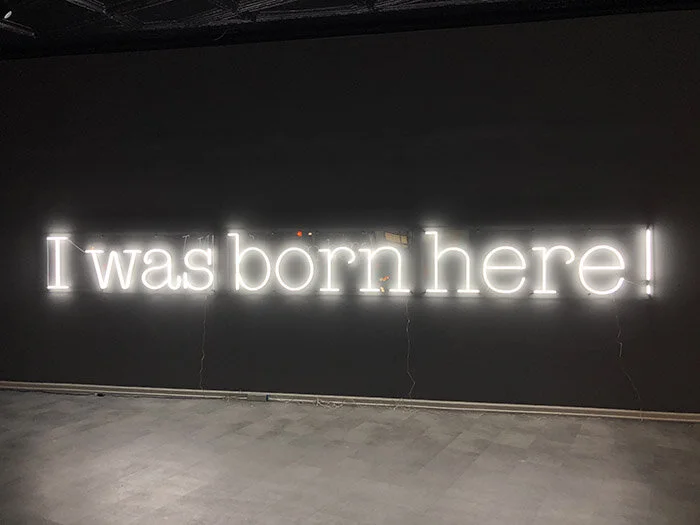

Olu Oguibe, I Was Born Here, LED lights. Installation view of Strange Names. Five Points Gallery, October 2020. Courtesy of Karl Goulet.

At Five Points Center for Visual Arts, the group exhibition Strange Names highlights the experiences of immigrants through the works of three artists: Hirokazu Fukawa, Olu Oguibe, and Joe Bun Keo.

Fukawa, an Associate Professor of Art at the University of Hartford, relocated to the United States in 1988 after experiencing political unrest following World War II in Japan. Nigerian-born Olu Oguibe fled civil war, landing first in Britain and later settling in the United States. Bun Keo’s parents moved to this country to escape the Khmer Rouge communist regime in Cambodia. Through the diverse works of these artists in this show, parallel feelings of alienation and compassion arise. Together, they point to longstanding tensions within this country about immigration that have recently become more contentious.

The youngest of the three, Bun Keo was born in the country, but his childhood was heavily influenced by the experiences of his parents. Manual labor, parenthood, and cultural identity are some of the recurring themes tackled by Bun Keo in his work. Often, his pieces present a meditation on linguistics. Subtle inaccuracies of language fascinate Bun Keo, who learned to speak English as a second language. These nuances are embedded in his installations, assembled from items from hardware or thrift stores. Divorced from their intended functions, things such as belts, bricks, and bags of uncooked rice feel out of context, prompting viewers to dig for their meaning.

This interview with Bun Keo focuses on his family’s history and how it has impacted his career as an artist.

[Jacquelyn Gleisner] Firstly, I wanted to extend warm congratulations to you and your family on the addition of your daughter. What a remarkable and bizarre time to welcome a new family member! Secondly, congratulations on the group exhibition Strange Names at Five Points Gallery. Tell me about the work that is on view in this show.

[Joe Bun Keo] Thank you, coffee is my best friend right now. She’s a little firecracker. Thank you again, I would like to express my gratitude to Judith McElhone and Karl Goulet of Five Points Gallery for their support of this exhibition. The work in this show is not a protest but a reflection of how the immigrant experience permeates our daily narratives and our artistic practices.

Installation view of Strange Names. Five Points Gallery, October 2020. Courtesy of Karl Goulet.

[JG] Your parents are refugees of the Khmer Rouge communist regime. Can you share more about their experiences before they fled Cambodia? Were they open about these experiences with you and your family members growing up?

[JBK] My family were poor farmers in rural Cambodia. They didn’t have much of childhood. They were raised to work. Education took a back seat to survival. My parents shared their hardships to instill in me and my sister a strong work ethic and resilience. Their trauma became our strength.

[JG] I’m interested to learn more about the connections between your work and the two other artists in the show. What threads weave your work together with those of Hirokazu Fukawa and Olu Oguibe, the other two artists in the show?

[JBK] There are generational differences, but the immigrant story resonates in us all. Our work reflects the journey, the displacement, and the discomfort at times of being immigrants or children of immigrants. Each piece isn’t necessarily centered or focusing solely on that experience, but aspects of it are visible through the narratives and concepts.

Installation view of Strange Names. Five Points Gallery, October 2020. Courtesy of Karl Goulet.

[JG] The exhibition statement talks about how this nation was founded on the idea of a haven for those who were not wanted elsewhere. There’s some truth to this, but the founding of this nation was also at the expense of those who were already inhabiting the land. As a second-generation American, I wondered about the way that you conceptualize the beginning of this country. How do your experiences give you a different perspective on the early history of this country?

[JBK] That is fact. We are on stolen land. Colonizers murdered, raped, and stripped indigenous people of their homes. Later, immigrants arrived in a world conquered by aggression and disregard. Nonetheless new immigrants, in addition to those of the displaced indigenous people, are the foundation of this nation. Colonizers and imperialists come to take and usurp; immigrants come to start anew and join a melting pot. My family wanted a blank slate. They were sick of living in fear. They believed America was that place. It has been marketed and pitched as such for as long as I have been alive, but now, that reputation doesn’t even exist. For goodness sake, we celebrate Indigenous Peoples’ Day on the day that commemorates the biggest culprits of cultural theft — Columbus. This nation needs to heal and take a hard look at itself in order to stop living in a selective version of reality.

Installation view of Strange Names. Five Points Gallery, October 2020. Courtesy of Karl Goulet.

[JG] Today the tension surrounding the rightful stewardship of the land reverberates in the experiences of immigrants — and of course, their offspring. Immigrants and their families sometimes called “foreigners,” carry this implied sense of being apart from the rest of the culture. Did the notion of being an “outsider” impact your trajectory as an artist?

[JBK] It always has: artists, in general, are outsiders because we view the world in a much more complex scope. I’ve always been a fish out of water. Unfortunately, the water is no longer there for me to even consider going back into. I’m just trying to adapt to hostile territory.

[JG] Over the past few months, we have witnessed the beginnings of what I hope are some radical changes within this country. How has the pandemic and subsequent protests impacted your practice?

[JBK] The impact is not just in my practice — it’s my life. My life and my practice are not separate. These radical changes should have happened long ago, but here we are still protesting the same issues. We pride ourselves of being sophisticated intellectual beings, but I disagree. We are the most primitive.

[JG] Do you have any upcoming shows or events or other news you’d like to share with readers?

[JBK] I’m in a public art exhibition coordinated by the Contemporary Galleries at the University of Connecticut called Silk Flowers.

Strange Names is on view at Five Points Gallery from October 9 until November 14, 2020.