Repost | The Demands of Dread Scott

Dread Scott. Sign of the Times, 2001. Screenprint; 39 x 39 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Dread Scott made the screenprint above in 2001, and — shamefully — the relevance of its message has only increased over the past two decades. When I interviewed Dread Scott in 2014 — the fact he was willing to meet with me an act of extreme generosity — he opened the conversation by stating, “The world is a great horror.” I think about this afternoon often, with gratitude to Scott, an artist whose works continue to confront some of the most horrific aspects of our culture, many of which have been resistant to change.

Scott scours history for examples of how change has taken root. Last November, Scott led a crew of nearly three hundred performers during the community-engaged artist performance and film production called Slave Rebellion Reenactment. Documented by filmmaker John Akomfrah, re-enactors wore clothing consistent with 19th-century French garments as they mounted horses, tracing the events of the German Coast Uprising of 1811. Over two days, enslaved people marched toward present-day New Orleans. The dream to gain independence and end slavery was not realized at this time. But Scott’s performance places this hope for freedom back into the public consciousness.

From this recent large-scale performance to his entry into the limelight during the 1989 controversy, Scott’s career has been committed to the idea that art can nudge history into a more equitable future.

Repost | The Demands of Dread Scott

Art21 Magazine | Nov 4, 2014

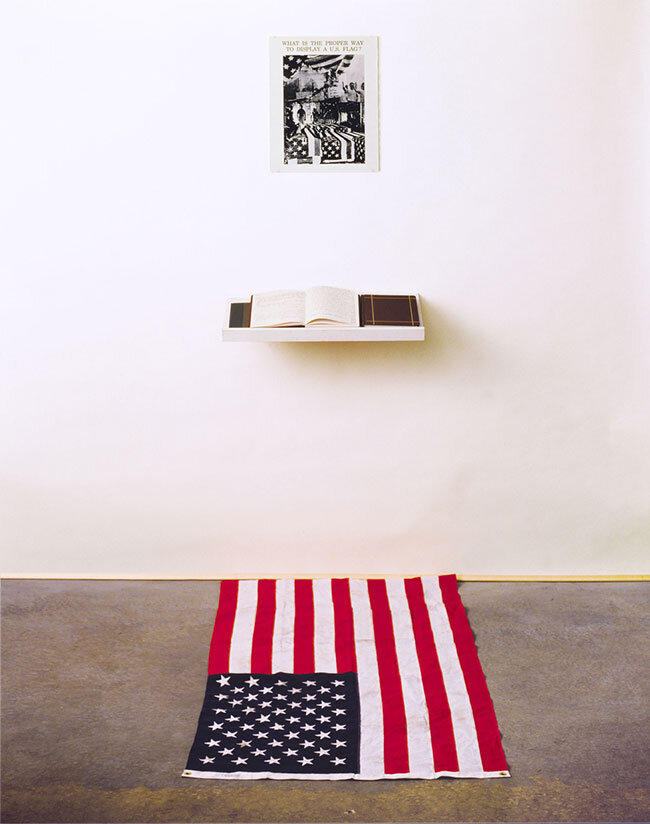

In 1989, the artist and activist Dread Scott incited national debate with his work, What Is the Proper Way to Display a US Flag? Scott’s installation, which included photos of flag-draped coffins and of South Korean students burning US flags, beckoned viewers to ponder the work’s titular question. Mulling over this, each participant stood on an American flag on the floor and wrote responses in a ledger. Yet President George H. W. Bush deemed the work disgraceful, and the US Senate passed legislation in protection of the American flag. In protest of the mandatory patriotism contained in the new law, Scott and three others elected to display the flag in an improper way: they burned flags on the steps of the Capitol in Washington, DC. Controversy flared and a Supreme Court case ensued. At the time, the artist, whose nom de plume recalls the 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford decision, was twenty-four years old.

Dread Scott. What is the Proper Way to Display a U.S. Flag?, 1988. Installation for audience participation: Silver gelatin print, books, pens, shelf, active audience, US flag; 80 x 28 x 12 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Twenty-five years later, I sat at a wooden table in Scott’s Fort Greene apartment as he described the gulf between his work and ideology before the controversial artwork. Scott’s bridge between form and content functioned as a conduit to the limelight. Moreover, the hybrid installation-performance and its fallout cemented Scott’s belief in constructing work that engages radically and meaningfully with society. The phrase “I make revolutionary art to propel history forward” begins his artist statement on his website.

And history needs to progress because, as Scott stated, “This world is a great horror.” [1] The Thirteenth Amendment to the US Constitution was adopted in 1865 and abolished slavery, yet this institution was entrenched in the foundation of this country and its trappings remain manifest. As evidence, Scott pointed to the recent death of Michael Brown, a young black man in a suburb of St. Louis, Missouri. On August 9, 2014, Brown was chased on foot and shot six times by Darren Wilson, a white police officer. In the wake of Brown’s death, protests and racial tensions escalated. While the fate of the officer is being decided by a grand jury and the FBI is investigating the incident for civil rights violations, Scott believes that artists should raise society’s awareness to this type of recurring sore.

After Michael Brown was killed, Scott tweeted an image: a piece called Sign of the Times that he had made following the shooting of a different black man, Amadou Diallo. In 1999, Diallo, a twenty-three-year-old immigrant from Guinea, was shot by four plainclothes New York City cops in the Bronx. A total of forty-one shots were fired; nineteen of those bullets struck Diallo. In response to this event, Scott created a screen print reminiscent of yellow-and-black traffic signs, with the text “Danger: Police in Area.” The fact that this piece could apply to a situation fifteen years later stresses the relevance and prescience of the ideas that inform Scott’s practice as an artist. “I don’t think art by itself is a revolution,” Scott explained, “but I think that it can contribute to people more substantially and fundamentally seeing a different world.” Artists can focus a lens for others to view the injustices of this world.

Dread Scott in his apartment, New York, 2014. Photo: Jacquelyn Gleisner.

Artists can project a glimpse of a better world, too. For example, in 2009 Scott worked with a dozen inner-city teenagers in Philadelphia to make a piece that imagined their futures. The installation, …Or Does it Explode?, was titled after the last line of the Langston Hughes poem, Harlem. The first line of this poem is a poignant query: “What happens to a dream deferred?” Scott echoed this inquiry in his interviews with the group of teens, and the installation culminated in twelve life-size photographic portraits of their responses. Commissioned and funded by ArtWorks!, the education program of the City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program, this public-art project was accompanied by audio that recorded the dreams and hopes of the group. One teenager wanted to become a philosopher and travel the world. Another aspired to become a social worker or lawyer but realistically admitted she would not be able to attend college because her high-school education had been subpar. The collection presented perspectives that were both lofty and an affront to the subtext of the American Dream, the belief that hard work will always lead to upward social mobility.

Because transcending their social class is impossible for some Americans, Scott positioned the installation’s life-size light boxes horizontally on the ground, like coffins. The morbid gesture suggested the grim futures for certain members of society. Scott referenced lyrics from “Things Done Changed” by the late rapper, Notorious B.I.G. (or Biggie): “If I wasn’t in the rap game / I’d probably have a key knee-deep in the crack game.” Biggie’s words outline two routes for inner-city youth: an improbable escape from social and economic hardships afforded by fame or, the more likely path, a hard-trodden life of crime fueled by drugs on the streets. Scott believes that for some youths, given the slim odds of achieving success as a rap star, breaking laws that do not appear to support their social class can seem a rational choice.

Dread Scott. …Or Does it Explode?, 2009. Duratrans prints, lightboxes, narrative audio; 28 feet 6 inches x 16 feet 4 inches x 1 foot. Courtesy the artist.

Capitalism does not profit all members of society equally, Scott asserts, and a society in which crime is perceived as a reasonable option for members from low-income backgrounds is indeed a horror. But Scott is optimistic. His challenge to others is to “consistently fight with everything you understand to bring the horrors of the world to an end.” Furthermore, Scott charges artists to “find ways to make rich, substantive work that will talk about these issues.” He began his revolution as a young art student with a bold question that morphed into a demand for change. Twenty-five years later, Scott is still asking hard questions.

[1]. All quotes from Dread Scott are from a conversation with the author on September 12, 2014.