Review | Hong Kong in Poor Images

Review | Hong Kong in Poor Images

Ely Center of Contemporary Art

January 12 – February 16, 2020

Nichole Licata

Hong Kong In Poor Images is a four-room show on display at the Ely Center for Contemporary Art exhibiting artwork based on the lifestyles and culture of this urban city. Curator Zeng Hong explains in her statement that the “spirit of the poor image” lives in the paintings, photographs, and films presented because the main goals of these artists is to help the viewer visualize the culture of Hong Kong firsthand, as opposed to “focusing on ‘aesthetics’ or craftsmanship.” They attempt to utilize the poor quality to create a more impactful message for viewers.

Entering the gallery, the floorboards creak, the air is stale, but every room is filled with natural light. The Ely Center is an old, refurbished two-story house with various sized rooms with Hong Kong in Poor Images on the first floor. In view of the entrance, there is a large carpeted U-shaped staircase that leads to another exhibition on the second floor.

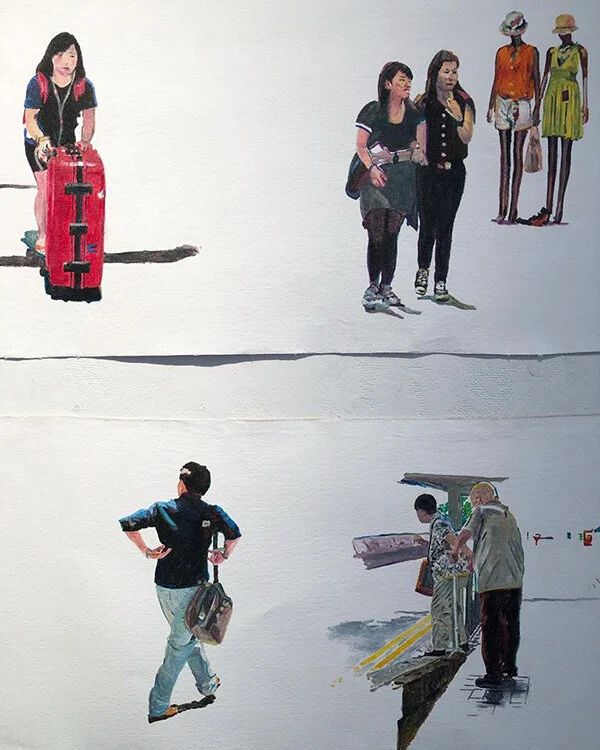

Stella Ying-chi Tang, People in the Streets of Hong Kong (2012).

Heading towards the first room left of the staircase, unframed acrylic paintings on canvas surround Hong’s statement on the walls. Stella Ying-chi Tang’s series of paintings, People in the Streets of Hong Kong (2012), contains representational figures based on photos from a digital camera she took of people in Hong Kong. They are stretched along three walls of one room for a total of five paintings that are thirty-eight by one-hundred-fifty centimeters in dimension. Having them arranged in this orientation makes the viewer almost “read” the paintings like a book. Every person—regardless of age or gender—is dressed and posed differently in various locations, going about their daily routines. Yet barely any information is given about the setting of all these figures placed next to one another.

Tang does this purposefully to make viewers feel as though they are getting lost within the huge “global metropolis” when seeing “the diversity of bodies and body language” in Hong Kong. This personally had an effect on me, as I focused on the details of each individual’s brightly colored clothes and posture; I kept moving left to right, wondering what each person is doing and where they are going. The negative space between figures in the paintings individualized each moment in time as if seeing it firsthand.

While Tang paints these Hong Kong residents beautifully, this series does not emphasize the meaning of the exhibition. These paintings appear extremely well-crafted; they do not possess the requisite “poor quality” described in the curatorial statement. Tang encapsulates the culture of the region and creates an aesthetically pleasing series of paintings, so initially, I thought this work did not fit in with the rest of the exhibition. But the meaning behind the work—quick impressions of different types of people—does.

Jamsen Sum-po Law, Walking the Walk (video still). Courtesy of the Ely Center of Contemporary Art.

Walking towards the next room in a tiny sectioned off corner, Linda Chiu-han Lai’s film Voices Seen, Images Heard (2009) is played on loop. The projection takes up almost the whole wall and contains Lai’s “self-dialogue of how to write the history” of Hong Kong. Scenes of the city and its denizens are intermittently interrupted with a black screen and white text that says, “This is Hong Kong,” with garbled industrial noises. Other scenes include shadowy blurred images.

Her low-resolution video was confusing. There is no clear beginning or end. It did not help that a nearby window also washed out the video. After reading the wall text, Lai’s message remained opaque. This installment definitely fits the name of Poor Images, but the video itself feels ambiguous and hard to decipher.

Across the foyer of this gallery is another room with seven chromogenic prints. Tang Kwok-hin’s series of photos Don’t Blame the Blossom (2018) is a journey throughout the streets of Hong Kong. Images include a birds-eye-view of a side street with parked cars, flyers suspended from the overhang of a local supermarket, a view into a restaurant from a window, children playing with a ball in a plaza, and two men on a scaffold in front of a village house. Every picture makes viewers feel they are peering into the everyday lives of these people. Kwok-hin’s unified and cohesive selection of C-prints gives viewers a richer, and more realistic, understanding of how people interact within this environment.

In the same room, Bryan Wai-ching Chung’s video Movement in Time, Part 2 (2019) is shown on a TV screen on top of a podium. It is comprised of a black background with four separate animations in each quadrant. In the top right, Chinese text flashes between white and shades of gray in an irregular pattern. Towards the top left part of the screen, a pixelated image appears in a wave-like fashion, and below it is an animation that seems like twenty-five clocks operating and flashing rapidly. In the bottom right corner, red lines move fluidly and quickly to replicate calligraphic characters in motion.

One of the more interesting and unusual videos in this exhibit, I spent a lot of time watching this to study how each section interacted with one another. Chung created this from motion data in fighting sequences in Hong Kong martial art films, which was put into an algorithm that matched it to a database of Chinese characters shown as animated writings. Those characters are sequences of lines of poetry but are not sensible enough to be read as an actual poem.

This work was my favorite part of the exhibition because of the artist’s process and how it was presented. With flashing lights and the stark contrast between the crimson red script, it takes time to fully analyze what is happening on the screen. It seems that its four parts do not make sense with one another, but after reading Chung’s description of the video, its meaning becomes understandable.

Hong Kong in Poor Images is an unusual show because of curator Zeng Hong’s message to her viewers. While it took several reads to fully understand her statement, ultimately these artists are attempting to allow viewers to take a closer look into the distinct cultural elements of this city instead of the name it has been given by larger corporations and the media. All the artists presented in the exhibit achieve this individually, however divided and disjointed the show seems as a whole.

Nichole Licata

Nichole Licata is a freshman at the University of New Haven. Born in Guangxi, China, Licata grew up in Bethpage, New York. As an Illustration major in the Honors Program, she aspires to become a professional Botanical Illustrator. Working part-time for a local florist from 2018-2020 inspired her to seek a profession related to this field. In high school, Licata participated in the philosophy debate team Ethics for three years as an alternate captain. Her team placed second overall in the regional Ethics Bowl and fourth in a national competition. She received a Senior High School Scholarship from the Art Supervisors Association in her local district. Graduating with a 4.0 GPA from high school, Licata is proud to have been accepted into the Honors Program at the University. Over the past three years, she has traveled to three different countries: China, France, and England. During these trips abroad, she immersed herself in Chinese, French, and British cultures. Exploring Asia for eleven days, she learned more about her heritage as a Chinese-American and increased her knowledge of Asian culture. The experience has encouraged her to weave those influences into her artwork.