Review | James Prosek: Art, Artifact, Artifice

Review | James Prosek: Art, Artifact, Artifice

Yale University Art Gallery

Through June 7

Jenna McIlwrath

In the current exhibition at the Yale University Art Gallery, James Prosek: Art, Artifact, Artifice, the award-winning artist, naturalist, and writer blends imagery from the natural world while confronting the conventions of its classification system. Featuring works from the collections in the Yale University Art Gallery, the Yale Center for British Art, and the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, Prosek challenges viewers to question the boundaries they impose on the three terms.

With original paintings from 2019 to items produced in eighteenth-century China, the exhibition consists of five rooms, organized among eight categories: “Naming Nature,” “The Myth of Order,” “Mark Making,” “The Color Spectrum,” “Representation and Artifice,” “The Spaces Between,” “Nature as Tool,” and “Hybridity.”

Philip Guston, Untitled [Square Boot], from Suite of 21 Drawings (1970). Ink on paper; sheet: 35.4 × 43.1 cm (13 15/16 × 16 15/16 in.).

The first room of the fourth-floor exhibition explores the theme of “Mark Making,” which underscores the importance of primitive artist tools—such as charcoal—while shining light on the handmade. Several inkjet prints are displayed next to bird eggs that seem to have inspired the adjacent prints, along with older objects, such as clay tablets from 6th century B.C. Babylonia that refers to birds.

The most eye-catching piece in this room, however, is an untitled work (1953) from the American artist David Smith (1906-1965). Composed of ink and tempera on paper with a tea-colored background, this painting contains a collection of abstract symbols: Smooth and rounded brush strokes create circles in a jet black hue. A light mauve shadow connects the majority of the symbols. As a whole, the composition is airy, with a decent amount of untouched space remaining on the paper.

Paul Gauguin, Paradise Lost , ca. 1890. Oil on canvas; 46 × 54.9 cm (18 1/8 × 21 5/8 in.).

The second room contains both “Naming Nature” and “The Myth of Order.” The former category parallels the naming process, emphasizing the need for human possession and control. Ink works from Philip Guston complicate the notion of possession. From Guston’s Suite of 21 Drawings (1970), these four works are all simplistic representations of things people normally possess: a hat, a boot, the cuff of a jacket, and a chair.

The “Myth of Order” highlights the human need to shape things into patterns for our own survival. Paul Gauguin’s 1890 Paradise Lost painting, an oil depiction of Eve living in harmony with wild animals, and related works are featured to help illustrate this point.

Helen Frankenthaler, Low Tide (1963). Oil on canvas, 213.4 × 207.6 × 2.5 cm (84 × 81 3/4 × 1 in.) framed: 216.9 × 210.5 × 3.8 cm (85 3/8 × 82 7/8 × 1 1/2 in.).

The spacious third room of the exhibition is home to “The Color Spectrum,” which equates the color spectrum to the evolutionary continuum. Neither has clear lines and the boundaries we have created are arbitrary. Low Tide (1963) by Helen Frankenthaler, an oil painting on a ginormous canvas, hangs next to the category description. Teal, periwinkle, powder and savoy blue, and grape juice stain purple make up what appears to be the silhouette of a large abstract Old English Sheepdog in the middle of the canvas, while royal yellow and cream cover the rest of the canvas.

James Prosek, Bird Spectrum (detail), (2019). Bird specimens. Courtesy the artist; specimens provided by the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. © James Prosek.

Paintings by artists such as Sol Le Witt and Mark Rothko fill the rest of the room, except for Bird Spectrum (2019) by James Prosek, a collection of bird specimens forming a long, wide line, all bearing identifying tags. Their feathers cover all the colors of the rainbow, arranged in order from brilliant red to deep purple.

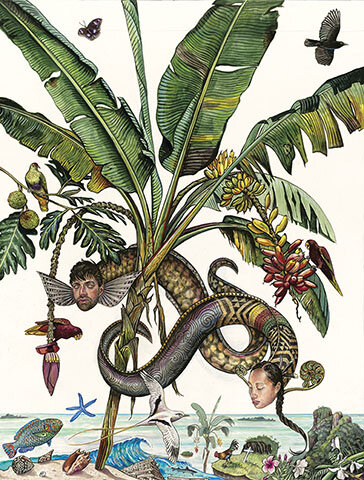

James Prosek, Study for Paradise Lost, Ponape (2019). Watercolor, gouache, colored pencil, and graphite on paper. Courtesy the artist and Waqas Wajahat, New York. © James Prosek.

Room four is long and narrow, like a hallway. The category for this room is not apparent, although the clear focus is on fish. An entire wall is lined with watercolor fish paintings by Prosek. Opposite of that are several glass cases, continuing the fish theme. One entire case displays Asian fishhooks and lures from the first half of the twentieth century. The last work in the room by Prosek, entitled Paradise Lost 2 (Ghost Orchids, Everglades) (2019), is a crudely constructed painting made with oil and acrylic on panel, ash branch, clay with oil and watercolor, and LED lights. This work has the craftsmanship of a child, as if an elementary schooler found a branch in their yard, bought some silk orchids, cardstock depicting a jungle with an alligator and some LED lights. Minimal effort appears to have been invested in making this disappointing diorama.

The fifth and final room introduces “Representation and Artifice,” which demonstrates the relationship between humans and nature, particularly the human desire to deceive the natural world. It would have made sense to include the previous room in this category; fish lures are made to trick fish into biting.

Next up is “The Spaces Between,” which visualizes the unseen connections of the universe. The Hundred Birds is a work of satin with silk embroidery from the nineteenth century (artist unknown). A dark beige, twisty tree with powder blue flowers is depicted above a blush rose bush. Covering the entire plane are birds of all kinds, such as chickens on the ground, parrots on branches and swallows in the air. All the colors seem to have a light beige undertone, giving the scene an intimate and calm feeling.

“Nature as Tool” and “Hybridity” are the two most peculiar categories. “Nature as Tool” imagines what nature would look like if it evolved to be useful to humans, with bird nests, woven baskets, and bones on display. The wildest works were in the same display case. Prosek’s Utility Composition No. 2 (2019) combines bird specimens with everyday human materials––a drill bit, pencils, fishhook, paintbrush, saw blade, and a sewing needle. The beaks of the small birds were replaced with these materials. What if birds evolved to have paintbrush beaks? Prosek lets us see firsthand.

James Prosek, Paradise Lost 1 (Burmese Python and Blue and Yellow Macaw, Everglades), (2019). Oil and acrylic on panel. Courtesy the artist and Waqas Wajahat, New York. © James Prosek.

Finally, “Hybridity” dreams up combinations of known animals presenting a vision of artifice; hybrids can be just as mystical as they are feared. Two pieces steal the attention in this section: Industrial Evolution (2012) and Flying Squirrels (2012), both taxidermal artworks by Prosek. Industrial Evolution is a beaver taxidermy with a chain saw chain placed along the outside of the tail. Flying Squirrels consists of a white squirrel taxidermy with duck wings and a black squirrel taxidermy with quail wings. What makes this one so interesting, is that flying squirrels already exist, except without wings. This work envisions what they would like if they had wings. It also shows the contrast in the good versus evil; one squirrel is white, the other is black.

James Prosek: Art, Artifact, Artifice dares to question the boundaries humans create around art and nature. “What would happen, if we stop putting things into neat categories and simply marvel at the wondrous and complex world of which we are a part?” Prosek asks viewers. According to the artist, art helps us see beyond the boundaries we place on nature. Art, Artifact, Artifice creates a lens into a boundary-free world.

Jenna McIlwrath

Jenna McIlwrath is a nineteen-year-old student and musician from Boston, Massachusetts. As a singer-songwriter, she spends her free time writing lyrics in notebooks and recording melodies in voice memos. She finds inspiration from personal struggles and aims to shed light on mental illness through her music. With an album in the works, McIlwrath currently has a single on major music platforms, such as Spotify and Apple Music. She interns in the summer at a music school near her home, where she works with kids to write songs and help them perform as a band. McIlwrath aspires to create a sustainable concert touring production company in the future. Her passion for the environment is parallel to her respect for all living things. A vegan for over four years, she is a strong advocate for animal rights and believes in living a life based on compassion for all beings. McIlwrath is currently a sophomore at the University of New Haven, pursuing a bachelor’s degree in Music and Sound Recording with a concentration in Music Industry. She is the secretary of her Audio Engineering Society chapter, treasurer and student government representative for Fully Charged Acapella, and is a member of the Music Industry Club.

![Philip Guston, Untitled [Square Boot], from Suite of 21 Drawings (1970). Ink on paper; sheet: 35.4 × 43.1 cm (13 15/16 × 16 15/16 in.).](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5bbcf46c11f7841ec6d0c9c5/1583181079357-NFHDRVWE0FRG7PW6ICL5/ag-obj-124398-001-pub-med.jpg)