Studio Visit | Felandus Thames

Studio Visit | Felandus Thames

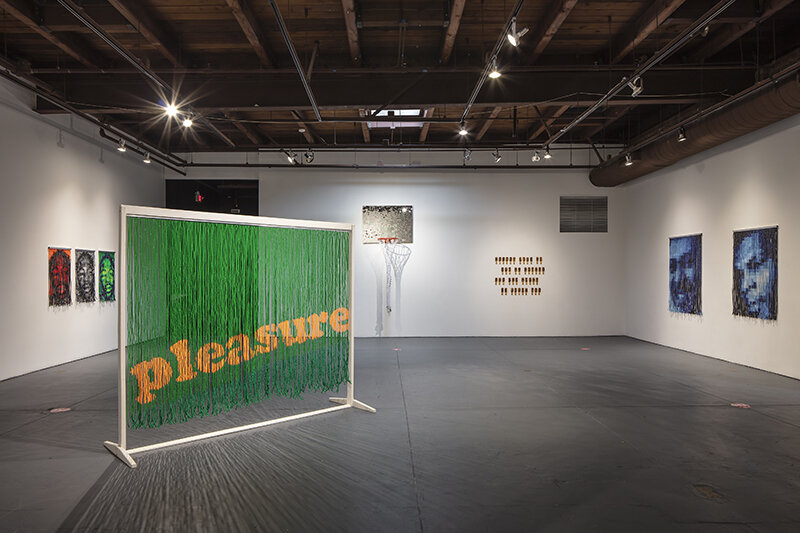

Installation view of The Things That Haunt Me Still. Real Art Ways, Feb. 13 - May 30, 2021. Photographer: Peter Brown.

Pleasure. This is the first word that viewers will connect with the work of Felandus Thames at his solo show The Things That Haunt Me Still at Real Art Ways. Bright orange beads pop against a vibrant kelly green backdrop in this central work. The bold, seraphic font alludes to the colors and diction of advertisements for Newport cigarettes from the 1980s. With their banal imagery, these ads often targeted African American consumers.

Yet in Thames’s Pleasure, the word sinks to the bottom of a beaded veil poised within a white freestanding frame. The implied heaviness hints at the disconnect between the meaning and application of the word within the product’s advertisements. The word also underscores one of the show’s themes — how different audiences access and relate to the portrayals of Black people in the media. Curated by David Borawski, Thames’s exhibition targets the intertwined issues of race and gender, sometimes by way of consumer culture.

Plans for The Things That Haunt Me Still began about two years ago, but many of the works in Thames’s solo show were made in the six months prior to its opening. That half-year was defined by the COVID-19 pandemic and racially-motivated protests — an unsettling timeframe that Thames has processed through his practice as an interdisciplinary artist. Throughout this time, Thames has often worked for twelve or thirteen hours straight, six days a week in his West Haven studio.

“Artists have long been imagined as highest on the pecking order of blue-collared workers,” Thames said. “However, the work of the artist is to erase notions of labor and deal with the economy of ideas. What separates us from theorists is the practical application of these ideas,” Thames added.

Still, there’s pleasure present in the act of making. “It’s my hands,” he explained. “And [viewers] often think about the relationship between the hand of the artist and the moments of beauty.”

Thames grew up in a creative household in Jackson, Mississippi. His dad painted, and his mom sewed. He and his two brothers played instruments and learned how to draw. He explained that this involvement with the arts was a form of acquiescence. “Growing up in the Post Civil Rights era in the urban south, many Black families viewed ‘Respectability Politics’ as a direct function of notions of the Middle Class,” Thames said. “My family saw a healthy relationship with the humanities as a direct function of that.”

For Thames, making art was more than a performance, and from an early age, he understood the pressure of pursuing a career in the arts. When he was accepted into an Advanced Placement program for visual art, Thames asked his high school teacher instructor to talk to his parents. He had applied without their permission, and he knew they would need encouragement. They wanted him to have a career that would be structured and stable — an accountant or something in healthcare, for instance.

With this idea of security on his mind, Thames began college at Jackson State University, a Historically Black University, as an architecture student — a field that presented a compromise. Architects are artistic and more importantly, employable. But by the end of the first semester, Thames had switched to double-major in fine art and graphic design. Along the way, he often paused his education to save money, working as a designer and museum preparator, among other roles.

A few months before graduation, Thames made a promise to his father. On the day of his death, Thames vowed to his father that he would attend one of the top graduate programs for art at Yale University. Later that year, he received a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree, debt-free, and then, a few months later, he enrolled in Yale’s School of Art in the Painting and Printmaking department.

One of the more important lessons from Thames’s first year in the program was the significance of process and media. “Traditional painting methods didn’t speak to the meaning of my work,” Thames reflected. Slowly, he distanced himself from the medium of painting by building installations with fiberglass mesh. He was seeking ways to implicate the viewer within his work. Meanwhile, many of his peers fixated on the glossy, fetishized surfaces that were popular at that time.

Installation view of The Things That Haunt Me Still. Real Art Ways, Feb. 13 - May 30, 2021. Photographer: Peter Brown.

Thames, on the other hand, focused on cultivating an unvarnished experience for his audience. “Recently I have been concerned with a return to my initial impulses as a young maker and the kinds of things that inspired me to become a creative,” he said. “I have been re-authoring the images from my childhood with intentions of removing the ‘white male gaze’ that’s associated with the history of photography. I’ve been using materials that are laden with the residue of memory in this endeavor.”

In his current show, several works cull from anonymous photographic sources. Living in American (Don King) is another example of a beaded work, but this one veers from consumer ads into portraiture. It draws a straight line between a pronounced incident of police brutality in 1991 to the present day.

“I was in high school when the Rodney King [beating] happened,” Thames said. “I remember watching the video [on television] and thinking, ‘I saw the same thing happen last week, and it didn’t make the news.’”

Nearly thirty years later, a viral video recorded George Floyd’s final gasps for breath in May, and this week, the murder trial for Derek Chauvin, the former police officer charged with Floyd’s death, will begin. There have been countless other deaths or instances of brutality that we haven’t seen and offenders who were never charged, Thames explained. The strings of beads mimic the seriality of violence against Black bodies.

A gradient of black, blue, and white beads creates King’s face, which has been closely cropped and appears pixelated from a distance. The sway of the long beaded strands interrupts the rigidity of the gridded image.

These shiny, plastic beads are hair beads. Another work includes jingles from a tambourine, heightening the experience of sound. The form references the mystical hippie partitions of the 1960s that harken from ancient Asian cultures, while the oversized face acts as an entry point for a private meditation on King’s public experience.

Installation view of The Things That Haunt Me Still. Real Art Ways, Feb. 13 - May 30, 2021. Photographer: Peter Brown.

To the right of this work, another work has been adapted from the likeness of another icon. In Predator and Prey (Mike Tyson), toxic perceptions of Black, male aggression undergird Thames’s portrayal of the professional boxer. Both the images from King and Tyson appear to have been taken from surveillance footage. The insidious feeling that these two men were being watched contributes to their trauma as tormented figures.

Across the room, Anita Hill’s face is rendered in shades of purple in one of the more personal works within the exhibition. For Thames, Hill functions as a surrogate for a family member who was assaulted. He learned about the experience when Dr. Christine Blasey Ford accused Brett Kavanaugh of sexual assault during his nomination for the Supreme Court in 2018.

Choosing to portray King and Hill magnifies the repetition of the recent injustices. The same year that the police beat up Rodney King, Hill testified before Congress about the sexual harassment she encountered as an aide for another Supreme Court appointee — Clarence Thomas. The repeated histories are mirrored in his repetitious process.

The allure of these beaded works stems in part from their formal strength. Thames approaches the beads in a painterly fashion. For example, the African King of Dubious Origins series seems monochromatic. They seem red, green, and black from afar, but up close, there are unexpected flashes of blue, purple, and other hues. The intricate and time-consuming act of adding each bead circles back to the idea of hidden labor.

There are also two multi-media pieces in the exhibition that relate to another form of labor — sports, specifically basketball. Lay Up #2 (Sports as Religion) places the viewer within the work in a direct way. The backboard of the basketball hoop is composed of small, mirrored tiles. In Motion in the Ocean, reconstituted basketball rims appear to be joined together in an extended curving line. The title comes from a euphemism about sex. Here, Thames mixes metaphors, fusing contrasting stereotypes of Black men with wry humor.

“I try to make work that would allow multiple audiences to access it.” He continued, “I have come to imagine this body of work as a diary of a latchkey kid.” Many of these works arose from his childhood memories — photographs and advertisements — that have been reclaimed through Thames’s painstaking process.

Installation view of The Things That Haunt Me Still. Real Art Ways, Feb. 13 - May 30, 2021. Photographer: Peter Brown.

Felandus Thames’s solo exhibition The Things That Haunt Me Still continues through May 30, 2021 at Real Art Ways. A Zoom panel discussion between Thames and writers Kiese Laymon (Heavy: An American Memoir, 2018) and Charlie R. Braxton (Cinders Rekindled, 2013) will be moderated by artist Noel W. Anderson on April 12 at 7 p.m. Register for the free event here.

All quotes from the artist are from a conversation with the author that took place over Zoom on March 17, 2021.