Review | Audible Bacillus

Review | Audible Bacillus

Ezra and Cecile Zilkha Gallery, Wesleyan University

wesleyan.edu

Through March 3, 2019

Audible Bacillus Installation view, Zilkha Gallery, Wesleyan University. Image: J. Gleisner.

Audible Bacillus presents the first curatorial effort in the Zilkha Gallery conceived by Benjamin Chaffee, newly appointed Associate Director of the Center for the Visual Arts at Wesleyan University. This imaginative group show opens a dialogue between the new curator and his community by way of the noisy chattering of our innards. The exhibition takes its name from the phenomenon of a rumbling stomach, the bacteria in the gut announcing their presence to the world outside them. Scientists understand that these bacteria—outnumbering our human cells by ten times—communicate with our brains through the vagus nerves, yet the exact method of sharing information is unclear. Chaffee employs these concepts as a metaphor for exploring similarly indecipherable systems of communication through the works of over a dozen contemporary artists. The fuzzy border between the self and non-self (or other), organism and co-organism, also bubbles to the surface, as language devolves into noise to a non-native speaker.

Chaffee holds a master’s degree from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in sound art, and he explained that many of the works he selected reflect his interest in this medium. From nearly anywhere inside the Zilkha Gallery, the song of birds can be heard, originating from two clear, glass cylinders, one upright and the other horizontally positioned on the floor. A piece by Mary Helena Clark (American, b. 1983) called Ligature (2017), is the source of the sprightly chirping, and these particular recordings are played for canaries raised in isolation. Absent other means, these birds learn to sing by listening to and mimicking these tapes, while potential anomalies amplified by acquiring song in this way remain silent to our human ears.

Mary Helena Clark, Ligature (2017). Glass cylinders, piezo discs, audio cable, medical tape, amplifier, media player, project box. 24 x 6 x 6 inches per cylinder. Image: J. Gleisner.

Centered on the back wall of the gallery, a dim screen plays a soundless animation that pertains to arcane depictions of sound. Other Transformations (2019) by lucky dragons, the collaborative duo of Los Angeles-based artists Sarah Rara and Luke Fischbeck, repackages the pair’s personal archive of graphic representations of music beyond a standardized notational system. Specific forms—a circle meant to signify the breath of a vocalist, per se—change shape on the screen, moving from one composer’s unique visualization of music to another, one abstraction mirrored in another non-literal iteration. From this mute and mutating sequence, viewers begin to question how—and if—an image can represent organized sound.

Across the gallery, another wall reproduces the text of Yoko Ono’s water talk (1967), a tender poem about the desire to delineate distinct boundaries of this liquid despite its indivisibility. You cannot hold a piece of water in your hand, but the human impulse is to identify with a measured amount. As “container minders,” Ono (Japanese, b. 1933) seems to think we prize an individual unit over the whole, amorphous body. Likewise we imagine we have complete control of our actions and thoughts, in lieu of acknowledging any unconscious yielding to the dynamic organisms living inside us. Unwittingly, we care for this microbiome because we can’t exist without it.

Audible Bacillus installation view with Yoko Ono, Candice Lin, and Josh Tonsfeldt (left to right). Image: J. Gleisner.

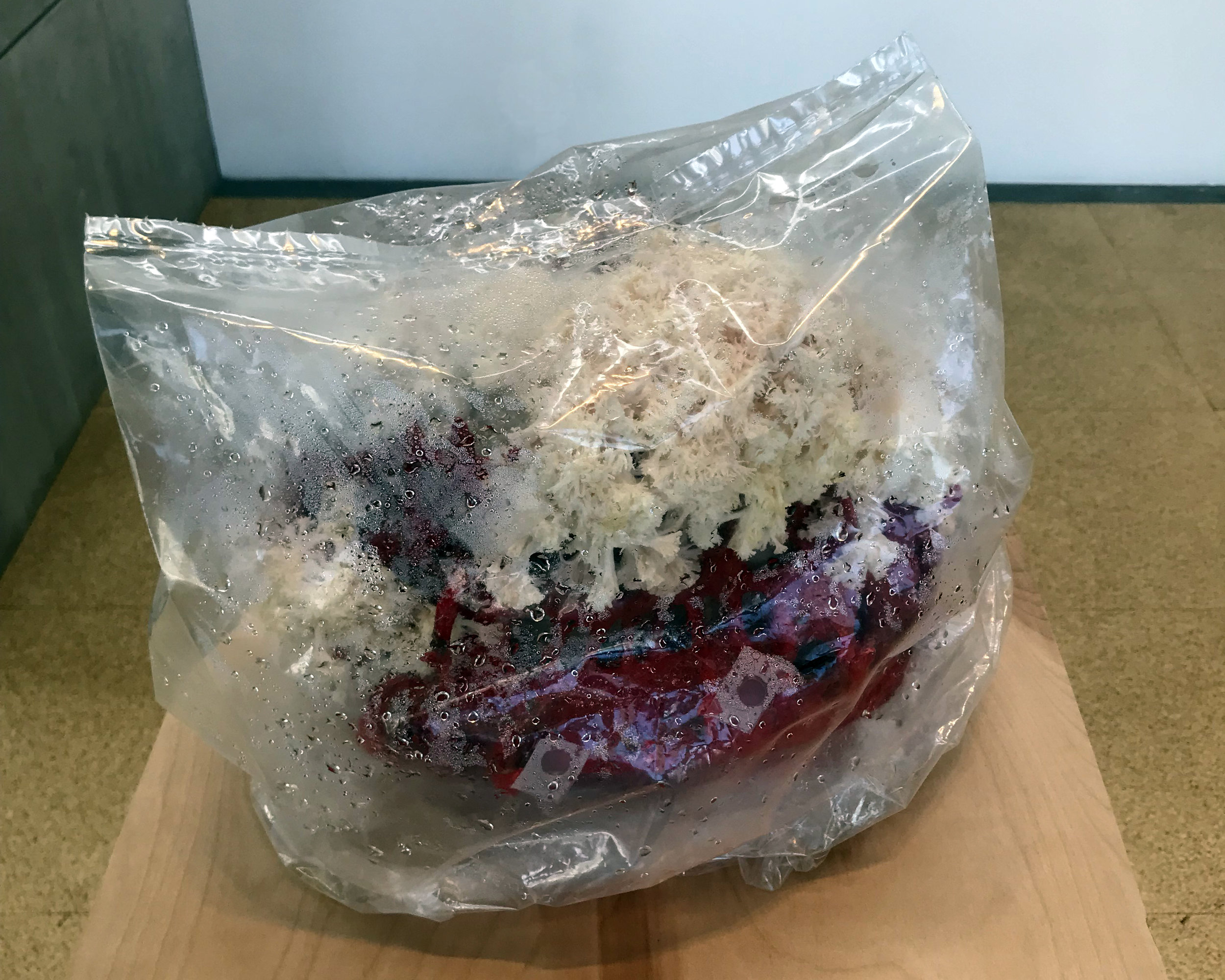

In similar fashion, Memory (Study #2) (2016) by Candice Lin (American, b. 1979), who is also based in Los Angeles, touches on empathy and dependence, albeit housed in an unlikely vessel. Growing inside of a plastic bag, Lion’s Mane Mushrooms burst from the top and sides of a porous red ceramic container. This protective covering makes a moist environment for the frilly fungi, which can be eaten or ingested to improve one’s cognitive and digestive health. Per Lin’s instructions, the mushroom starter kit is nourished with the distilled urine of those involved with the hosting of the exhibition, and this process is repeated with new groups as the work travels to different venues. Distillation removes bacteria, but the color remains and the odor is intensified. The title implies that memories or other forms of somatic knowledge are perhaps transmitted to the organism from the “communal piss” as the mushroom is cared for over the duration of the show. Meaningfully, this makeshift community becomes tantamount to the work itself.

Candice Lin, Memory (Study #2), (2016). Distilled communal piss of the people hosting the work, glass jar, Lion’s mane mushrooms in substrate, plastic. 9 1/2 x 13 x 9 inches. Image: J. Gleisner.

A veritable community of narrators, who may or may not be distinct voices within the same entity, confuse the central narrative of Warm, Warm, Warm Spring Mouths (2013) by British filmmaker Ed Atkins (b. 1982). Inside Atkins’s luscious digital realm, a nude avatar with long hair wears white earbuds, a prop that underscores the aura of alienation. “I don’t want to hear any news on the radio about the weather on the weekend,” a snippet from a poem by Gilbert Sorrentino (American, 1929-2006), repeats throughout the video, which is projected on a large wall within a separate room. The phrase becomes more emphatic as this avatar recites it. With hyper-realized textures like the impossibly weightless flow of the character’s long locks and his uncanny facial twitches, the protagonist lures viewers closer to him and then taps the surface of an imagined screen (the video is entirely animated), a taunt that accentuates the divide between our world and his.

Atkin’s intoxicating digital world is balanced by several earthy additions: stromatolites on loan from the Joe Webb Peoples Museum and Collections at Wesleyan, many of unknown source and age though some date to the Late Cambrian period (roughly 490 million years ago). Placed on wood plinths, these dark, fossilized rocks provide physical evidence of bacterial growth and anchor the show to the notion of deep time. (They also tie nicely to the limestone walls of the soaring space.) Patterns and intricate crazing appear on the surfaces of these rocks, pointing to numerous, alternating waves of life and death. As an example, during the Great Oxidation Event around 2.5 billion years ago, an exponential uptick in cyanobacteria filled the atmosphere with oxygen, a waste product made by these organisms. While advantageous to other lifeforms, oxygen had the adverse effect of poisoning these bacteria, abetting their own mass extinction. In the context of this exhibition, the stromatolites—beautiful and ancient—hint at the looming possibility of a future extinction.

Stromatolite. Hoyt Limestone, Saratoga Springs, New York. 5 x 13 7/8 x 7 inches. Late Cambrian (~490 millions years old). On loan from the Joe Webb Peoples Museum and Collections, Earth and Environmental Sciences, Wesleyan University. Image: J. Gleisner.

Chaffee softly echos this concern in his curatorial statement, writing: “In a present time of mounting ecological crisis, Audible Bacillus investigates the potential of bringing awareness to our internal intersubjectivity.” Yet the heaviness of this implication does not permeate the exhibition, lightened by its birdsong soundtrack. Chaffee’s approach to the quirky metaphor is more conceptual, less corporal. The title sounds scientific, but the works largely are not. Taken as a whole, these artists advocate erratic modes of transferring and receiving knowledge, calling attention to the limits of our minds, the expanse within our bodies, and the mysterious liaison of the two.

lucky dragons: Other Transformations Performance

Sunday, March 3, 2019 at 1pm

Ezra and Cecile Zilkha Gallery

This performance will incorporate video projection by the Los Angeles-based experimental music group lucky dragons, an ongoing collaboration between Sarah Rara and Luke Fischbeck. The performance will feature a piece that lucky dragons have collaborated on with Wesleyan students. The group researches forms of participation and dissent, purposefully working towards a better understanding of existing ecologies through performances, publications, recordings, and public art, including sounds created in collaboration with the audience. The name “lucky dragons” is borrowed from a fishing vessel that was caught in the fallout from H-bomb tests in the mid-1950s, an incident which sparked international outcry and gave birth to the worldwide anti-nuclear movement.

The show continues through Sunday, March 3.